3.3.2. SSH - Secure Shell¶

Secure Shell (SSH) is a protocol to access other computers. It was invented in 1995 to make the old methods more secure but on first glance it still behaves similar to remote shell or telnet from the eighties: You can connect to a remote computer to enter commands in a terminal. In the simplest case you will just type the name of the computer you want to connect to:

ssh username@servername.domain

However SSH has become much more powerful than this if you know how to use it correctly. So in this section we will try to go through all the helpful features you should know when working remotely.

But first we need to talk a bit about security, especially encryption.

Asymmetric Encryption¶

One cornerstone technology of the current internet is asymmetric cryptography, or public-key cryptography. When browsing the web we all use it constantly without caring about it but it’s also important for the efficient usage of SSH so we need to go through some key features of it.

The idea behind asymmetric encryption is to have two distinct, different keys for encryption. One key can encrypt the message and then only the other key can decrypt the message.

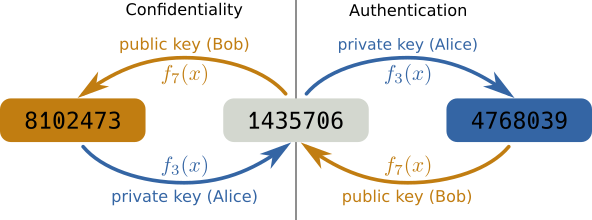

A very simple example, consider a string of numbers from 1435706. Now for

encryption we could just “add” a value to each of this digits and take the

modulus by 10 to get another digit

Now if we choose as keys \(A=3\) and \(B=7\) then we can “encrypt” the

message by applying \(f_A(x)\) on each digit to get the encrypted message

4768039. And we can decrypt it again by applying \(f_B(x)\) to get the

original message 1435706. This also works by first applying \(f_B(x)\)

and then \(f_A(x)\)

If we encrypt a message with one key we need to use the other key to decrypt the message again and vice versa. Now this example is obviously way too simple but this is actually rather close to the RSA algorithm still used today.

In practice, we will now keep one of these keys private and publish the other. Let’s say we have two people, Alice and Bob and Alice owns the private key and Bob has the public key. Then with this key pair they can perform two things:

Fig. 3.15 The two use cases of public/private encryption using our very simple example.¶

- Confidentiality

Bob can send confidential information only intended for Alice by encrypting it with the public key. Only Alice has the private key to decrypt it and nobody else can see the content of the message (left side of Fig. 3.15).

- Authentication

To establish the identity of Alice, Bob gives Alice a message to encrypt with her private key. Bob can then decrypt it with his public key to be sure he talks to Alice as only she would have been able to encrypt the message (right side of Fig. 3.15).

The second part here is the one you are using almost everywhere in the internet: Every https connection on the internet uses this principle to make sure that the server claiming to be “netflix.com” is actually the real netflix server. And this is also what we use for SSH connections.

Warning

While the public key can be shared freely it is critical that the private key remains private. If someone gains access to your private key they can impersonate you in the digital world and get access to a lot of your resources.

Key points

asymmetric cryptography has two keys, a private and a public key

it can be used to establish the identity of the owner of the private key

the private key should be kept as safe as possible.

SSH Basics¶

Now back to SSH: When we connect to a server using SSH it will use the same method to establish the identity of the server. So when you connect for the first time SSH will ask you if you know this computer. So if you type

ssh <desyusername>@bastion.desy.de

(and replace <desyusername> by your DESY username) for the first time you

should see something like

The authenticity of host 'bastion.desy.de (131.169.5.82)' can't be established.

RSA key fingerprint is SHA256:WbkI/Ko+FdCbIAVn6ky2odyWxCvCL3+5XqWSZQ6PynE.

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no)?

This means that ssh doesn’t have the public key of bastion.desy.de which is

called the “host key” so it cannot be sure you connect to the right server. It’s

usually fine to just say yes, it will only ask you the first time and remember

this decision. So after you enter yes you will get a message like

Warning: Permanently added 'bastion.desy.de' (RSA) to the list of known hosts.

which is perfectly normal. In the next step the server will ask you for your password and after you entered that you should see a command line prompt and are now connected.

Once you are connected the next important step is to disconnect, just type

exit and press return and your connection will be closed. If you’re very

impatient you can also press Ctrl-D as a shortcut.

Warning

Don’t run long-running and CPU or memory heavy jobs on login nodes like KEKCC and DESY where they have a dedicated batch systems (e.g. Gbasf2, LSF or htcondor). The login nodes are shared resources for all users and it’s not very polite and mostly also not permitted to occupy them with calculations that could be done on dedicated machines.

Exercise

Login to bastion.desy.de, verify that the login succeeded with the

hostname command and log out again.

See also

One final thing about host keys: After you connected to a server, ssh remembers the host key and will verify it on each connection. So you might see something like this:

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ @ WARNING: REMOTE HOST IDENTIFICATION HAS CHANGED! @ @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ IT IS POSSIBLE THAT SOMEONE IS DOING SOMETHING NASTY! Someone could be eavesdropping on you right now (man-in-the-middle attack)! It is also possible that a host key has just been changed. The fingerprint for the RSA key sent by the remote host is SHA256:zyIMwlji8jqtD+UuSFuknQmevQPAUCiT39BfH/NrIbA. Please contact your system administrator.This means the host presented a different key than it used to. This can sometimes happen if the server you want to connect to was reinstalled. So if you know that the server was reinstalled or upgraded you can tell ssh to forget the previous host key. For example to forget the host key for

bastion.desy.dejust usessh-keygen -R bastion.desy.de

Copying Files

In addition to just connection to a remote shell we can also ssh to copy files

from one computer to another. Very similar to the cp command there is a

scp command for “Secure Copy”. To specify a file on a server just precede

the filename with the ssh connection string followed by a colon:

scp desyusername@bastion.desy.de:/etc/motd bastion-message

This will copy the file /etc/motd to your local computer into the current

directory. In the same way

scp bastion-message desyusername@bastion.desy.de:~/

will copy the file bastion-message from your local directory into your home

directory on bastion.desy.de.

Exercise

Copy a file from your local computer to your home directory on

bastion.desy.de

Hint

You can use the touch command to create empty files

Exercise

Copy a file from your home directory on bastion.desy.de to you local

directory

Question

How can we copy full directories with all files at once?

Hint

Try man scp

Solution

Supply -r to scp: scp -r desy:~/plots . will try to copy the full

directory plots on the remote machine to your current directory

However for more efficient copying of large amount of files you should consider

using rsync

Nested SSH connections

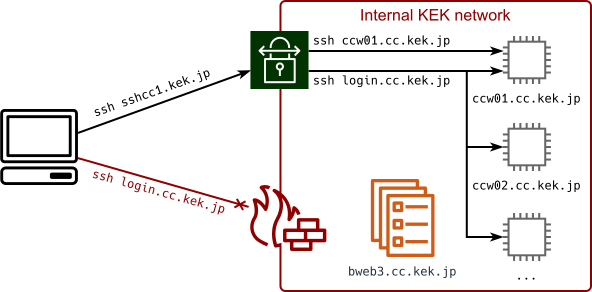

You can also use ssh inside an ssh connection to “jump” from machine to machine. This sometimes is necessary as not all computers can be connected to directly from the internet. For example the login node for the KEK computing center cannot be accessed directly if your are not in the KEK network or using VPN. The KEK network is rather complex so a very simplified layout is shown in Fig. 3.16.

Fig. 3.16 Very simplified layout of the KEK network.¶

Note

It is possible for your home institute to get direct access to KEK network so you might not be affected by this restriction while at work.

So unless you are using VPN or are at KEK you most likely need to connect to the

gateway servers first, either sshcc1.kek.jp or sshcc2.kek.jp

ssh username@sshcc1.kek.jp

Warning

Your username on KEKCC is not necessarily the same as your DESY username.

and once this connection is established you can login to KEKCC from this gateway server.

ssh username@login.cc.kek.jp

Warning

This second step needs to be done in the terminal connected to the gateway server

The initial password for

login.cc.kek.jpis not the same as that ofsshcc1.kek.jp.

Now you should be connected to KEKCC but you needed to enter two commands. And trying to copy files from KEKCC to your home machine becomes very complicated as you would have copy them in multiple steps as well so this is clearly not yet the optimal solution.

Key points

simple connection to a server is just done by

ssh username@servernamescpcan be used to copy files from and to remote computersyou can jump between hosts by executing ssh in a ssh connection

ssh uses host keys to ensure the identity of the server you connect to

Debugging¶

If you run into trouble in one of the following sections it can be very

instructive to switch on debugging output by using the -v option of ssh:

ssh -v username@servername

Once you have created a configuration file (next section) it can also sometimes

be helpful to disable it to rule out this source of error. This can be done

by using the -F option to specify a blank config file:

ssh -F /dev/null username@servername

SSH Configuration File¶

Now you can already connect to a server but if your username or the server name

is long you will have to type all of this every time you connect. Luckily we can

automate this using the SSH configuration file .ssh/config in your home

directory. Usually this file doesn’t exist but you can simply create an empty

file with that name.

The syntax of the configuration file is very simple. It’s just the name of a configuration option followed by it’s value. For example, to send periodic status updates which might help keep connections from disconnecting we can simply write the following in the file:

1# try to keep the connection alive, this avoids connection timeouts [S10]

2ServerAliveInterval 60 # [E10]

Note

Marker comments in the solution code

If you are wondering about comments like [S10] or [E10] in the code

snippets that we include in our tutorials: You can completely ignore them.

In case you are curious about their meaning: Sometimes we want to show only

a small part of a larger file. Copying the code or referencing the lines by

line numbers is a bit unstable (what if someone changes the code and

forgets to update the rest of the documentation?), so we use these tags to

mark the beginning and end of a subset of lines to be included in the

documentation.

But more importantly we can also define “hosts” to connect to and settings that should only apply for these hosts

1Host desy # [S20]

2 User YOUR_DESY_USERNAME

3 Hostname bastion.desy.de # [E20]

This now allows us to just execute ssh desy and the correct username and

full hostname are taken from the configuration file. This will also work with

scp so now you can just use the shorter version

scp desy:/etc/mtod bastion-message

to copy a file from the desy login server. This now also allows us to automate the login to KEKCC via the gateway server

1Host kekcc # [S30]

2 User YOUR_KEKCC_USERNAME

3 Hostname login.cc.kek.jp

4 Compression yes

5 # Don't connect directly but rather via the gateway server

6 ProxyJump sshcc1.kek.jp

7

8Host sshcc1.kek.jp # [S40]

9 User YOUR_SSHLOGIN_USERNAME # [E30]

The line containing ProxyJump tells ssh to not directly connect to the host

but first connect to the gateway host and then connect from there. We could make

this more complicated if needed by also adding a ProxyJump to the gateway server

configuration if we need to perform even more jumps. You should now be able to

login to KEKCC by just typing ssh kekcc and also copy files directly with

scp. But you will have to enter your password two times, once when

connecting to the gateway server and then when connecting to the KEKCC machine.

In case of ProxyJump trouble

The ProxyJump directive was introduced in OpenSSH 7.3. If you get an

error message Bad configuration option: proxyjump, please check if

you can update your SSH client.

While we definitely recommend you to get an up-to-date system that can use

the newer version, a quick workaround is to replace the ProxyJump line

with the following (using ProxyCommand):

ProxyCommand ssh hostname -W %h:%p

Where hostname should be the server you jump through, so

sshcc1.kek.jp in our case.

Exercise

Add a working kekcc configuration to your config file and verify that

you can login to kekcc by simply writing ssh kekcc

Hint

Create the config file and take the above snippet. But make sure you replace your own usernames for both servers

Key points

SSH configuration file is in

.ssh/configIt allows us to automate and configure ssh

We can define short names to connect to servers

We can automate jumping between hosts

Key Based Authentication¶

As you have seen there is a lot of entering your password, especially when jumping between hosts. Time to take care of that. Remember when we explained asymmetric encryption? SSH can use it to authenticate you to a server. This is usually safer and more convenient than using the password directly.

Note

Key based login doesn’t work to all servers. Most notable exception for us is DESY as they have a different security system called kerberos which is incompatible with key based login. However for DESY one can obtain a kerberos token instead which will have almost the same effect.

Creating a key pair

First, we need to create a private/public key pair to be used for SSH, called an

identity. We want to do this on your local machine. There is an easy way to

do this by just calling ssh-keygen. Without any options this will just

create a private/public key pair we can use but you might at least give it a

comment string so that you can identify the key easier.

ssh-keygen -C "Alice's Laptop"

This will prompt your for a file name, by default it should offer

.ssh/id_rsa in your home directory. If you do not already have a key then

just choose this. This will then be your default ssh identity and will be used

by default. Otherwise you can choose any filename you like and you can create as

many keys as you want but then you will have to tell ssh manually to use them.

It is advisable to put them in the .ssh directory but in theory you can put them

anywhere.

Warning

If you already have a key in your .ssh directory this might overwrite

the existing key and cause problems on existing logins. Only overwrite the

existing key if you are sure you don’t need the old one

Next, it will ask you for a passphrase to protect the key. While technically you can create keys without a passphrase you should never do so as it would make it way to easy for others to get access to your key. This passphrase is not related to your account passwords and doesn’t need to be changed but you should choose something safe, preferably a sequence of random words. Don’t worry, you don’t have to type it all the time. After that it should just print some information on the key. Congratulations, you have created your very own SSH identity.

Question

Where is the public key stored?

Hint

Check the output of ssh-keygen

Solution

In a file with the same name as the private key but .pub in the end.

Question (optional)

The default key type is to use “rsa”. What types are possible for a key?

Hint

Try man ssh-keygen or for more information google “ssh key types”

Solution

There should be RSA, DSA, ECDSA and Ed25519

However, DSA has been found unsafe and there are some concerns about ECDSA so the only real options are RSA and Ed25519. Ed25519 was added later and should be more secure but is not supported on very old versions of SSH.

Using your new key

Now that you have a key we want to use it. If you chose the default name, ssh

will offer it to the remote server automatically. If you didn’t choose the

default name you need to tell ssh to use this key. While you can just tell ssh

which identity to use with the -i parameter each time you run it, the best way

to do this is again the configuration file. You can even tell ssh to not try to

use the password at all but just the listed keys.

1Host sshcc1.kek.jp # [S40]

2 User YOUR_SSHLOGIN_USERNAME # [E30]

3 # NB: change the path to the IdentityFile to point to your own SSH key.

4 IdentityFile ~/.ssh/id_kekccgateway

5 IdentitiesOnly yes # [E40]

But if the remote server doesn’t know your identity it will reject it. So we

need to give the public key to the remote server. This is very simple, all

private keys you want to be able to login to a server should have their public

keys in .ssh/authorized_keys on the server. Just the contents of the

.pub files one after another. And there is a program available to create

this file. We just have to call it for each server we want to be able to login

with this key.

ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/id_rsa sshcc1.kek.jp

ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/id_rsa kekcc

Note

If you created the key in a different file you need to change the filename

given with the -i parameters. You can also omit the -i <identity>

option and ssh-copy-id will copy all public keys it can find.

Once that is done you should be able to login to KEKCC with only the key password. And on most machines ssh will automatically remember the passphrase during the session so you should only be asked to enter the passphrase one or maybe not at all if you already used the key recently.

Note

If ssh does ask you for your passphrase every time you might need to check

or configure your ssh-agent, the process that remembers the keys.

You need to repeat these steps from all machines you work from, so your laptop and your workstation if you have both: Each machine you “own” should have it’s own private/public key pair and those should be known to the servers you want to login to.

Making keys available on other machines

Finally, you usually don’t want to have private keys present on systems you don’t really have control over for security reasons. But even more important that would require us to keep track of too many key pairs. So usually we avoid having keys on servers like KEKCC. But sometimes, especially when using git, you might need or want keys to be available on these machines as well.

The best thing to do here is “Agent forwarding”: You tell ssh “please make the

keys I have on this machine available while connect to another machine”. This is

done very easily, either by adding -A to the ssh call or by adding

ForwardAgent Yes to the configuration file, either globally or on a per

host basis

Now after connecting you should be able to use your keys as if you were working

on your local machine. You can also inspect the keys available: ssh keeps

identities in an “authentication agent” for easy use. They are usually added the

first time they are used and then kept during the session. You can inspect and

modify this list of keys with the command ssh-add.

ssh-add <identityfile>to add a key to the agentssh-addto add all default keys (.ssh/id_rsa,.ssh/id_ed25519, …)ssh-add -lto list all keys currently known.ssh-add -d <identityfile>orssh-add -Dto delete one or all keys from the agent

Note

On MacOSX you need to add the following lines to the configuration file to enable agent forwarding

UseKeychain yes

AddKeysToAgent yes

(see this note for technical details)

Key points

ssh-keygencan be used to create private/public key pairs for authenticationssh-copy-idcan be used to copy the public key to the server to enable login via the private keywhich keys to use for which server can be configured in the configuration file

Agent forwarding can be used to make your local private keys available on the server you connect.

ssh-addallows you to add, list or remove identities from the agent

Port Forwarding¶

One of the last topics we need to discuss is the ability of SSH to do port forwarding. For this we first need to quickly explain what a port is: In computer networks you need two things to connect to a computer, its address and a port number. The address identifies which machine to talk to and the port number is just a simple number between 1 and 65535 to identify the service or program to talk to.

Which service uses which port number is not fully fixed so in theory we could run anything on any given port number but that would make the internet very complicated. So there is a set of “well known” port numbers which are used by default. For example, ssh uses port 22 by default and when browsing the web the https connections are on port 443 while the older, un-encrypted http is on port 80.

Now sometimes you might want to have a connection other than ssh to a machine

like the KEKCC login node that is not reachable. For example to reach a

web server like http://bweb3.cc.kek.jp that is only reachable inside the kek

network we need to connect to port 80 on the machine bweb3.cc.kek.jp

ssh can help us do that: we can instruct it to make something like a tunnel and route all the network traffic through its encrypted channel. The most common case for this is called local port forwarding: ssh creates opens port on the local machine and forwards all requests to connect to this one to another machine on the other end of the ssh connection. So getting back to the example:

ssh -L 8080:bweb3.cc.kek.jp:80 kekcc

This will open a connection to kekcc and the local port 8080. Any connection to

this port is then forwarded to bweb3.cc.kek.jp on port 80. So now to connect

to bweb3 we can open our local web browser and enter http://localhost:8080

and we should see it open the correct webpage.

Note that the 8080 in the local side can be chosen freely but only one program can open a port at any given time and you can only use ports above 1024 unless you have administrator privileges. 8080 is a “typical” port used for forwardings and is usually free. But any number is fine.

Question

How would the command look like if I want to open https://software.belle2.org

via a connection to bastion.desy.de? What do I need to type in my

web browser?

Hint

Make sure to choose the correct port

Solution

We need to run ssh -L 8080:software.belle2.org:443 desy and then type

https://localhost:8080 in the browser.

Programs that open ports on the target machine

One special case is running programs on the other side that directly open a port on the machine you’re working on for you to connect. The most prominent example in our field are Jupyter notebooks which offer a very nice python interface via web browser.

Warning

Opening a port is not user specific but opens the port visible to all users on the network. So whenever you open a port to listen to connections you should make sure it cannot be misused. Jupyter does this for you with passwords or token strings so you don’t need to worry in this specific case.

Note

DESY offers a direct weblogin to jupyter notebooks so the following is not necessary for DESY

Now you can tell jupyter notebooks which port to use but this time we run it on the KEKCC computers and there might be other users there so it can be a bit tricky to find an open port number. This means you should not just use “8080”. You should pick a random number between 1025 and 65535 for yourself.

Now we can connect to kekcc and forward this port number to the same number on the connected host. In this example we’ll keep 8080 but you should really pick your own number.

ssh -L 8080:localhost:8080 kekcc

In this case localhost means “whatever is called the local machine on the

remote side of the connection”. Once that is done we can try to start a jupyter

notebook on kekcc

source /cvmfs/belle.cern.ch/tools/b2setup release-05-00-01

jupyter notebook --port=8080 --no-browser

This should print a bit of information including a bit at the end that looks like this:

Or copy and paste one of these URLs:

http://localhost:8080/?token=...

Now you just need to make sure that the number is the same as you chose. If that

is not the case then the port you chose is already occupied and you need to stop

the notebook (press Ctrl-C), disconnect ssh and try with a different number.

If it is the same number you’re all good and you can just copy-paste the full

link (including the characters after token=) into your web browser and you

should see a notebook interface open up.

Key points

each network connection consists of a host and a port number

port forwarding allows to connect to other services via ssh

ssh -L localport:remotehost:remoteport serverwill forward all connections tolocalporton the local machine to whatever is calledremotehostat portremoteportonserverthis allows to open jupyter notebooks on kekcc or other computing centers

Additional Tips and Tricks (Optional)¶

By now you hopefully know all the things necessary to comfortably work with ssh and configure it to your liking. There are a few more things that can make working with ssh even more comfortable so we just collect them here for people interested in this.

rsync for file transfers

Very often one might want to synchronize a folder from a server with a local

machine. You already downloaded most of it but now you created a few new plots

and running scp -r would copy everything again unless you really specify

just the new files.

There is a program to solve exactly this problem called rsync. By default it

works on folders and will only transmit what is necessary. The most common use

case is

rsync -vaz server:/folder/ localfolder

which will efficiently copy everything in folder on server and put it in

the directory localfolder (beware, it matters whether or not you put a slash

at the end of the target)/ The most common options are

- -v

verbose mode, print file names as they are copied

- -a

archive mode, copy everything recursively and preserve file times and permissions

- -z

compress data while transmitting it

- -n

Only show which files would be copied instead of copying. Useful to check everything works as expected before starting a big copy

- --exclude

exclude the given files from copying, useful for logfiles you might not need

- --delete

delete everything in

localfolderthat is not in the source folder on the server. This is great to keep an exact copy but can be dangerous as files created locally might get lost

So to create an exact copy of a directory but excluding the logs subdirectory we could use

rsync -vaz --exclude=logs --delete server:/folder/ localfolder

Editing files over SSH

There are multiple ways to show files on a system connected to by ssh as if they were local files. For example

there is

sshfswhich lets you connect the files on a remote machine via the command line. Once it’s installed you can just runsshfs [user@]hostname:[directory] mountpoint. There even is a windows version.on Linux when using Gnome in the file browser there is a “+ Other locations” in left pane at the bottom. This should bring up a “Connect to Server” field where you can enter any ssh host in the form

ssh://username@host/folderand gnome will let you see the files on that host. See here for more information but this works similar in other desktop environments.In addition many editors or development environments have their own support to work on a remote machine via ssh. There is a guide on confluence explaining the setup for some of them.

SSH multiplexing

ssh allows us to have multiple sessions over the same connection: You connect once and all subsequent connections go over the same connection. This can speed up connection times and also reduces password prompts if key based authentication doesn’t work. All we have to do is put the following in the configuration file

1ControlMaster auto

2ControlPath ~/.ssh/%r@%h:%p.control

3ControlPersist 30m

And when connecting ssh will automatically create a control path that can be used by other connections and will keep the connection alive for 30m after we closed the last ssh session.

This also allows to add port forwards to an existing connection: once you are

connected to a server you can run ssh -fNL localport:remotehost:remoteport

server locally in a different terminal to add a port forwarding.

If you really want to close the connection to a server you will have to run

ssh -O exit server and ssh will close the channel completely.

sshuttle for advanced forwarding

There is an additional tool called sshuttle. You can only run it on machines where you have administration privileges but then it allows to use ssh to transparently connect your whole laptop to the network. This is then basically identical to a VPN connection.

Location aware SSH config file

Sometimes you want to have your SSH config depend on where you are with your laptop. For example, while at KEK you don’t need to jump through the gateway. This is indeed possible and explained in detail on B2 Questions.

Using a terminal multiplexer (e.g. tmux, screen)

When you loose your ssh connection or your terminal window is closed, all processes that had been running in that terminal are also killed. This can be frustrating if it is a long-running process such compilation or a dataset download.

To avoid this you can use a terminal multiplexer program such as GNU screen or the newer and more feature-rich tmux. Both are pre-installed on KEKCC and NAF.

Hint

For computational jobs like processing a steering file, use a batch submission system instead (see this warning).

These programs create one or multiple new terminal sessions within your terminal, and these sessions run independently of the original terminal, even if it exits. You just have to re-connect and re-attach the old screen or tmux session. A terminal multiplexer allows for example to

Start a process (e.g. a download or compilation) on your work computer, log out (which detaches the session) go home and from your home desktop / notebook re-attach the session and check how your process is doing.

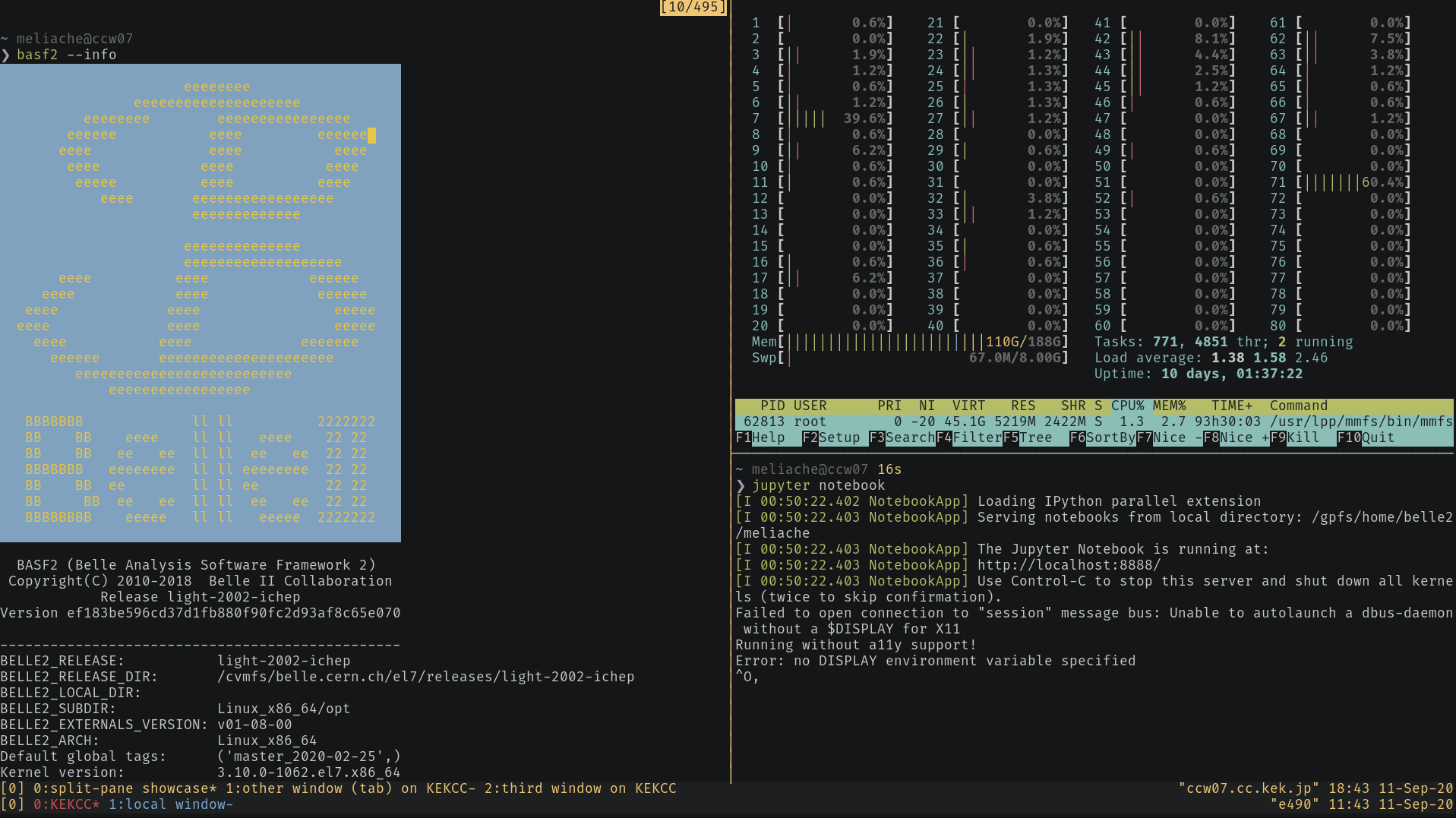

Having multiple interactive shells in parallel on a remote host, without needing to open multiple terminals and connecting from each one separately. Think of it like having multiple remote “tabs”. Tmux can also act as a terminal window manager and arrange them side-by-side. This can be useful e.g. for running a process in one pane and monitoring the processor load via htop.

Fig. 3.17 Tmux running in the local terminal and on KEKCC with multiple windows and panes.¶

If you don’t know either programs yet: learn how to use (the newer) tmux. Check out the official getting started guide from its wiki or one of the various googable online guides such as this one. And I also recommend keeping a cheat sheet in your bookmarks. The commands that you need for the most basic use-case are

- tmux new-session

Creates and attaches a new tmux session. This is also the default behaviour when just entering the

tmux. However, thenew-sessionsubcommand allows for additional options such as naming sessions (seetmux new-session --help).- tmux kill-session

Kills the current tmux session. Use this when you finish your work and don’t require your session anymore, it is a polite thing to do on shared resources like login nodes.

- tmux detach

Detaches the current tmux session, so that you return your original terminal session, but the tmux session keeps running in the background. This happens automatically when you loose your connection or your terminal is closed.

- tmux attach

Short form:

tmux a. Attaches a running but detached tmux session. When you log into a cluster like KEKCC or NAF to attach your previous tmux session, make sure are on exactly the same host as the one in which you started the initial tmux session.

All these commands take optional arguments to be able to handle multiple sessions and there are many more useful tmux commands than those listed here, for example if you want to have multiple windows (tmux “tabs”) and panes in a tmux. To see those, check out the documentation links above, where you will also find keyboard shortcuts for most of them.

Question

Why should I keep track of the exact host on which the terminal multiplexer is run and how do I do that?

Hint

Check out the output of the hostname command in a computing cluster like

KEKCC. Why is it different from the hostname that you used to login (the

Hostname line in your ssh config)? Could you have found out the host name without typing

any commands? How can you change the specific host?

Solution

When you connect to a computing cluster like KEKCC via a login node, e.g.

login.cc.kek.jp, you are connected to a random host (also called “node”,

i.e. an individual server) in that cluster for load-balancing purposes.

You can check the full host name with the hostname command. But you

can also see the first part of the hostname (the current node)

in your shell prompt (the string at the beginning of the command line).

If you disconnect and reconnect to the login node, you can be connected to a

different node, but your terminal multiplexer will still be running on the

old host, so you will have to connect to that specific host which it is

running on. From within the computing cluster, you can usually just use the

node name for the ssh connection. For example, if your tmux session is

running on ccw01.cc.kek.jp, but you have been connected to ccw02,

from there you can simply use

ssh ccw01

to connect to the other node. Alternatively, you can directly connect to a specific host instead of the login node, but for that you might need to extend your ssh config to also use a gateway server for the specific nodes in the cluster, e.g. for the KEKCC:

1# Configuration for directly connecting to specific KEKCC nodes [S50]

2# useful for connecting to a terminal multiplexer on a specific node

3Host ccw?? ccx??

4 HostName %h.cc.kek.jp

5 User YOUR_KEKCC_USERNAME

6 Compression yes

7 ProxyJump sshcc1.kek.jp # [E50]

Then ssh ccw01 will also work from outside KEKCC.

Stuck? We can help!

If you get stuck or have any questions to the online book material, the #starterkit-workshop channel in our chat is full of nice people who will provide fast help.

Refer to Collaborative Tools. for other places to get help if you have specific or detailed questions about your own analysis.

Improving things!

If you know how to do it, we recommend you to report bugs and other requests

with JIRA. Make sure to use the

documentation-training component of the Belle II Software project.

If you just want to give very quick feedback, use the last box “Quick feedback”.

Please make sure to be as precise as possible to make it easier for us to fix things! So for example:

typos (where?)

missing bits of information (what?)

bugs (what did you do? what goes wrong?)

too hard exercises (which one?)

etc.

If you are familiar with git and want to create your first pull request for the software, take a look at How to contribute. We’d be happy to have you on the team!

Quick feedback!

Author(s) of this lesson

Martin Ritter, Michael Eliachevitch